What caused Pakistan’s deadly floods? From melting glaciers to ‘monster’ monsoon

As one third of Pakistan is feared to be underwater following historic floods, experts tell Stuti Mishra how the climate crisis is changing the monsoon pattern in south Asia and making deadly deluges more likely

Hotter air, an unusually heavy monsoon, melting glaciers and a poverty-stricken population living with infrastructure incapable of protecting it – the recent devastating floods in Pakistan were due to a number of factors. But the most important cause is, undeniably, the climate crisis.

South Asia has always been a victim of a hostile climate, but this year is turning out to be one of the worst for the region.

First, India and Pakistan were hit by the worst heatwave on record – made 30 times more likely due to the climate crisis – and now, multiple cycles of heavy downpours since June have sparked calamitous flooding, leaving one third of Pakistan underwater.

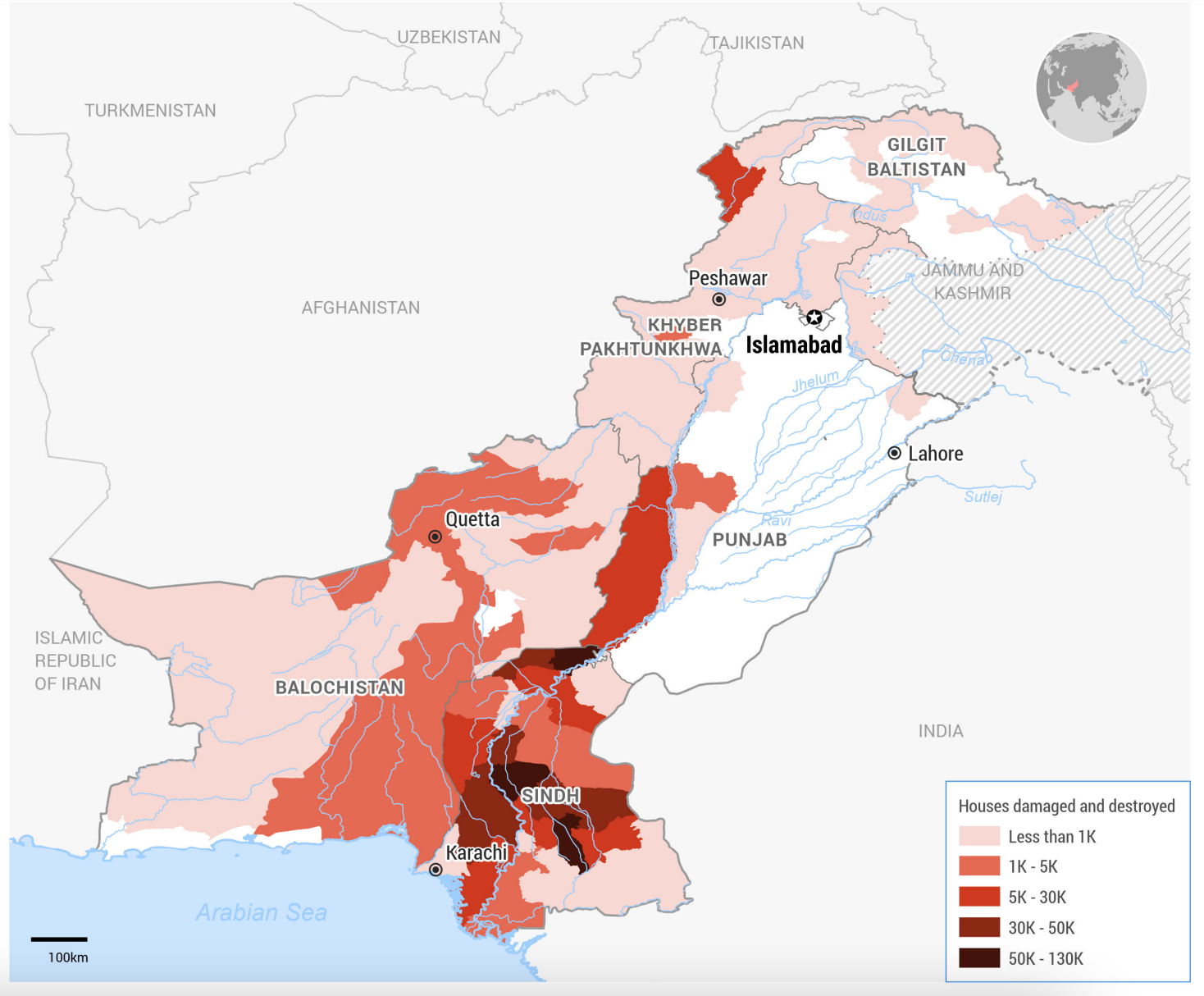

More than 1,191 people, including 399 children, have been killed so far, while 33 million people, or 15 per cent of the country’s 220 million population, have been affected.

“Monster monsoon” and “monsoon on steroids” are some of the terms being used to describe the rainfall, which has also devastated neighbouring Bangladesh and India this year.

The entire region is responsible for only a minuscule level of carbon emissions, with Pakistan and Bangladesh producing less than 1 per cent, but it is a “climate crisis hotspot”, as highlighted recently by UN secretary general António Guterres and previously in reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Early estimates put the damage from Pakistan’s floods at more than $10bn (£8.6bn).

“Pakistan has never seen an unbroken cycle of monsoon [rains] like this,” said Sherry Rehman, Pakistan’s climate change minister. “Eight weeks of non-stop torrents have left huge swathes of the country underwater. This is a deluge from all sides.”

Experts say the climate crisis is almost certainly responsible for these extremes, but there are several factors at play behind the massive scale of destruction.

Changing pattern of rainfall

Pakistan has received nearly 190 per cent more rain than the 30-year average in the quarter from June to August this year, totalling 390.7mm (15.38 inches). July was the wettest month for the region on record since 1961.

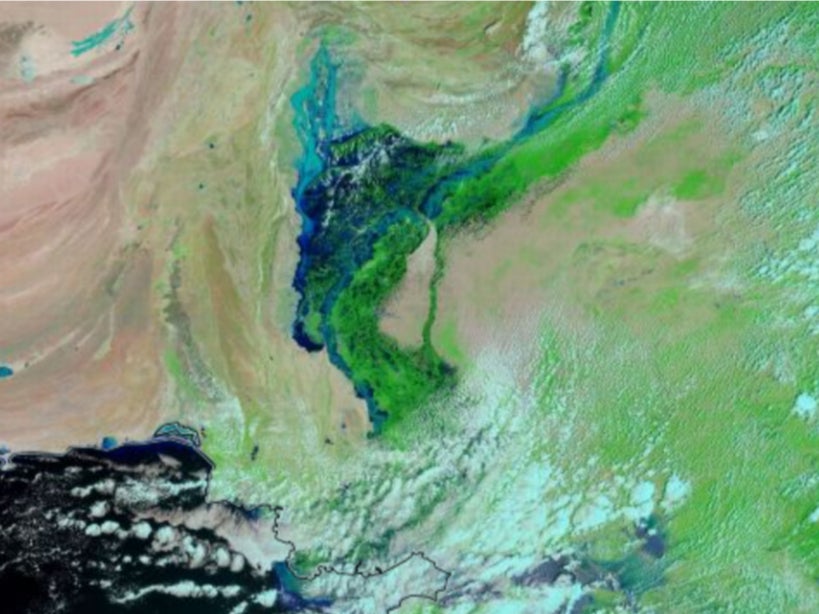

Sindh, with a population of 50 million, has been hit the hardest, getting 466 per cent more rain than the 30-year average. Major rivers such as the Indus are overflowing and low-lying areas around it have turned into swamps.

Satellite images show some parts of the province look like an inland sea with only patches of trees or raised roads visible.

Changes in rainfall patterns were expected as the region became hotter, because warmer air holds more moisture.

Surface air temperature has increased in the past century all over Asia, causing stronger, more frequent and longer heatwaves. Both India and Pakistan witnessed their highest temperatures on record this year during the deadly heatwave in April and May.

With a warming planet, such episodes are likely to become much more common in the coming years. The climate crisis “is very likely to have played a role” in these floods, according to Dr Friederike Otto, climatologist and co-lead of World Weather Attribution (WWA), an international effort to analyse and communicate the possible influence of global heating on extreme weather events.

“Historical observations show a recent increase in heavy rainfall and a decrease in moderate rainfall in the south Asian monsoon region,” she told The Independent. “And models project that these intense rainfall episodes will become more frequent, so we definitely expect to see more of these events in coming years.”

But meteorologists are citing concerns over changes in the track of monsoon weather systems across the region as well, and climate crisis is to be blamed for this, according to an analysis by Delhi-based Climate Trends.

There’s an unusual trend in the monsoon pattern in the region, which contributed to increased rainfall in Pakistan – a trend that has increasingly become visible over the last five years, said Mahesh Palawat, vice president of meteorology and climate change at Delhi-based Skymet Weather Services.

Mr Palawat said there had been abnormal trends in a weather system called “monsoon depressions” during this period. These are atmospheric vortices that produce a large fraction of south Asia’s rainfall as well as many of its extreme rainfall events.

“The two back-to-back monsoon depressions [low-pressure system in the monsoon] travelled right from the Bay of Bengal via central India to south Sindh and Balochistan in Pakistan,” Mr Palawat said. “It is a rare event – we usually do not see weather systems travelling in such a direction.”

While the easterly winds have been pushing these systems towards Pakistan, winds from the west were approaching the region from the Arabian Sea.

The convergence of these opposite air masses has trapped the weather system over the Sindh region and Balochistan for a long time, the meteorologist explained, resulting in torrential showers.

Since the region is arid and the geography of the land mass does not allow it to absorb huge amounts of water quickly, flash flooding was triggered.

The phenomenon can be “very well attributed to climate change, which has altered the track of monsoon systems, and they are now travelling in a more westerly direction through central parts of India”, Mr Palawat added.

Higher than average sea surface temperatures over the Indian Ocean, which modulates regional weather and climate over the Indian subcontinent, are leading to more evaporation, which means more moisture and more rain.

Role of melting glaciers

The long-term melting of the glaciers of the Himalayas, already worsened by the record heatwave this year, also exacerbated flash flooding in Pakistan as more water raced downhill throughout the summer to contribute to the deluge.

Pakistan is home to more than 7,200 glaciers, more than anywhere outside the poles. They are a source for rivers that account for about 75 per cent of the stored water supply in the country.

Melting of glaciers is another impact of a warming planet. As snowfall reduces and temperatures get high in summer due to climate change, glaciers are unable to regain the mass they have lost and are shrinking, say researchers.

A 2021 study found that the Himalayas – one of the main mountain ranges in the country – is losing ice at a rate that is at least 10 times higher than the average over past centuries.

“We have the largest number of glaciers outside the polar region, and this affects us,” climate minister Rehman told Associated Press earlier this week. “Instead of keeping their majesty and preserving them for posterity and nature, we are seeing them melt.”

This problem is further compounded by rampant deforestation, which is closely linked to unplanned development in the global South. Countries with limited resources have had to prioritise development and poverty alleviation, sometimes at the cost of ecological damage.

However, such climate catastrophes are forcing the world to rethink. Developing countries are being forced to take tough decisions to prioritise climate action and resilience even as a lack of proper climate-resilient infrastructure continues to pose serious hurdles.

Need for climate finance

Experts believe the changes brought by the climate crisis are here to stay and will propel extreme weather events over the entire south Asian region despite its limited contribution to the problem.

While the world talks about mitigating the impact and adapting to changes, the unfortunate reality is that it is impossible to adapt to extreme weather events, which will result in loss of lives and property and pose long-term challenges.

“During the last six months, the whole of south Asia has been reporting a series of extreme weather events. While Bangladesh, Pakistan and India have battled severe floods, China is reeling under massive drought conditions. These are big onsets of climate change,” said Dr Anjal Prakash, research director at the Bharti Institute of Public Policy and IPCC lead author.

“We never know when we will be caught off guard, no matter what we do. We will never be able to fully prove ourselves,” he added. “The only [solution for] us is rescue operations, but for that you would need money.”

Poor infrastructural development in the region has also played a key role in the scale of damage.

Most houses destroyed in Pakistan were in low-lying areas. Afghanistan suffered through massive destruction this monsoon as well, with hundreds of houses destroyed because poverty-stricken people were living in houses made of mud and stones.

Even government infrastructure such as dams and reservoirs were “woefully unprepared” in Pakistan, explained Auroop Ganguly, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northeastern University.

“Weather and hydrologic hazards, such as floods, do not usually turn into disasters unless there are infrastructural vulnerabilities and societal exposure,” Mr Ganguly told The Independent. “This is as true in south Asia... as in the US – where Hurricane Katrina induced floods in New Orleans in 2005 –or, indeed, anywhere in the world.”

Mr Ganguly said that “making lifeline infrastructures such as transportation, water distribution, power and communications networks” more robust and resilient could minimise the impact of such events.

However, building resilience also requires money.

Pakistan’s economy has already been struggling, with the recent floods only increasing challenges. Food inflation is high and prices are expected to climb as large swathes of agricultural land have either suffered from intense heat or flooding. The country is, in fact, considering buying vegetables from arch-rival India.

These challenges aren’t there only for Pakistan but stand true for a majority of countries in the global South, making the issue of climate finance – a form of reparations from rich countries to poor countries for the damage already wrought on the climate – an urgent requirement ahead of the upcoming Cop27 summit. But rich nations have so far failed to honour their pledges.

“All these events call for climate justice, becasue climate change was not the creation of people of south Asian countries. Some of these countries are either carbon-neutral or carbon-negative,” Dr Prakash added.

“Our carbon footprint is 1.9 tonnes, which is one of the lowest compared with the global average, which is four tonnes. South Asian countries must come up with coordinated voices and make the climate noise for funds, but it is not happening right now.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments